We have already studied the science of all the ten Principal Upaniṣads (Daśopaniṣads). Now, in this article we take up for study the Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad which does not belong to those ten, but is considered at par with them in view of the significance of its spiritual expositions.

The stream of thoughts therein, however, appears to have a deflection from that of the Daśopaniṣads, in respect of the mode of conception and style of presentation. Nevertheless, this Upaniṣad takes the ancient spiritual postulations further forward by adducing clarifications and making a few new assertions. We will see the details in the course of our study.

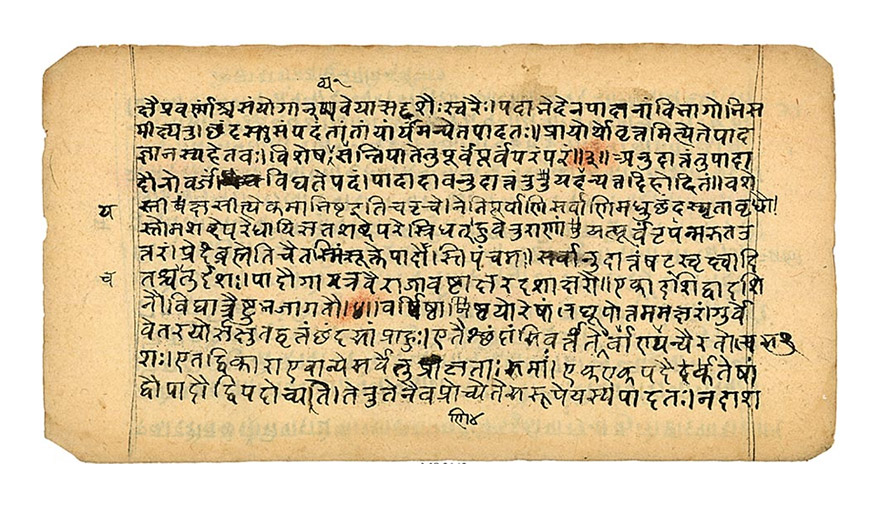

This Upaniṣad belongs to Kṛṣṇa Yajurveda and was expounded by Ṛsi Śvetāśvatara. It has got six chapters; a verse is identified by the chapter number followed by the verse number. The Upaniṣad opens with an enquiry into the ultimate cause of all, presented as being made by a group of Brahmavādins who are already Brahmavits. Brahmavādin is a person who asserts that all things are to be identified with Brahma and Brahmavit is a knower of Brahma. A group of such people raises a doubt whether Brahma is really the ultimate principle. They start an enquiry to settle the doubt. The first chapter deals with this enquiry and its findings. Let us see the first verse:

ब्रह्मवादिनो वदन्ति

किं कारणं ब्रहम कुतः स्म जाता केन जीवाम क्व च संप्रतिष्ठाः |

अधिष्ठिताः केन सुखेतरेषु वर्तामहे ब्रह्मविदो व्यवस्थाम् || 1.1 ||

brahmavādino vadanti

kiṃ kāraṇaṃ brahama kutaḥ sma jātā kena jīvāma kva ca saṃpratiṣṭhāḥ;

adhiṣṭhitāḥ kena sukhetareṣu vartāmahe brahmavido vyavasthām. (1.1)

Word meaning: brahmavādinaḥ- Brahmavādins; vadanti- say:

kiṃ kāraṇaṃ – by what cause; brahama – (is) Brahma? kutaḥ- from where; sma jātā – we are born; kena- by what; jīvāma- live; kva ca – and where; saṃpratiṣṭhāḥ- supported, established; adhiṣṭhitāḥ kena – regulated by or depending upon whom; sukhetareṣu- in pleasure and pain; vartāmahe- we get along, live on; brahmavidaḥ- knowers of Brahma; vyavasthām- in steadiness, composure.

Verse meaning: Brahmavādins say thus:

By what cause is Brahma? Whence are we born? By what do we live? Where are we established? Depending upon whose power, do we, the knowers of Brahman, remain in composure during the dual experiences of pleasure and pain?

It is very important that these questions are raised by Brahmavits. They know what Brahma is and are Brahmavādins too. So, their questions carry much philosophical importance. Even though they know Brahma and abide by that knowledge in their lives, they still doubt the extent of status of Brahma as a cause. To them, it is not the ultimate cause from which beings arise, by which they are sustained and on which they are established. They feel that there is some ultimate principle beyond Brahma facilitating all these things; their enquiry is to know that principle, the knowledge of which, according to them, enables the Brahmavits to maintain equanimity in the face of both pleasure and pain. Thus, they start the enquiry. The progress of their thoughts is given in the next verse:

कालः स्वभावो नियतिर्यदृच्छा भूतानि योनिः पुरुष इति चिन्त्या |

संयोग एषां न त्वात्मभावात् आत्माप्यनीशः सुखदुःखहेतोः || 1.2 ||

kālaḥ svabhāvo niyatiryadṛcchā bhūtāni yoniḥ puruṣa iti cintyā;

saṃyoga eṣāṃ na tvātmabhāvāt ātmāpyanīśaḥ sukhaduḥkhahetoḥ. (1.2)

Word meaning: kālaḥ- Time; svabhāvaḥ- Nature; niyatiḥ- destiny; yadṛcchā- chance; bhūtāni- the five fundamental elements (Pañcabhūtas); yoniḥ- the source of birth; puruṣa- the source of seed (germ); iti cintyā – these are to be considered;

saṃyoga- combination; eṣāṃ- of these; na tu – if not; ātmabhāvāt- by appearance of Ātmā; ātmāpi (Ātmā api) – though Ātmā is; anīśaḥ- not the ruler of; sukhaduḥkhahetoḥ- of the cause of happiness and misery.

Verse meaning: Time, Nature, destiny, chance, Pañcabhūtas, the source of birth, the source of seed – these are all to be considered (in the enquiry into the cause). It (the origin, etc. mentioned in verse 1.1) may be due to a combination of all these. If not, it must be by appearance of Ātmā, though Ātmā is not the ruler administering the cause of happiness and misery.

Evidently, Brahmavādins are considering many possible options. The final suggestion however is regarding appearance of Ātmā; but, at the same time they recognise that Ātmā is not the dispenser of happiness and misery which are mere outputs of wavering perceptions (which do not affect sthitaprajñas – men with composure). Yoni and Puruṣa here represent the female and male counterparts in the couple giving birth to new beings.

The pondering of the Brahmavādins culminates in a valuable finding which we can see in verse 1.3:

ते ध्यानयोगानुगता अपश्यन् देवात्मशक्तिं स्वगुणैर्निगूढाम् |

यः कारणानि निखिलानि तानि कालात्मयुक्तान्यधितिष्ठत्येकः || 1.3 ||

te dhyānayogānugatā apaśyan devātmaśaktiṃ svaguṇairnigūḍhām;

yaḥ kāraṇāni nikhilāni tāni kālātmayuktānyadhitiṣṭhatyekaḥ. (1.3)

Word meanings: te- they; dhyānayoga- profound meditation; anugatā- being absorbed in; apaśyan- recognised, realised; devātmaśaktiṃ- the divine power of Ātmā; svaguṇaiḥ- by own Guṇas; rnigūḍhām- veiled; yaḥ- who; kāraṇāni- the causes; nikhilāni- entire; tāni- those; kālātmayuktāni- conditioned by time; adhitiṣṭhati- control, superintend; ekaḥ- the one (without a second).

Verse meaning: Through the path of profound meditation they recognised the divine power of Ātmā, veiled by the Guṇas of its own projection; He, the only one without a second, encompasses and superintends all those causes which are conditioned by time.

The Brahmavādins finally found what they sought for; they realised that everything here is a projection of Ātmā and He is veiled by this projection consisting of Guṇas. It is because of this veil that He is not conspicuous. Bṛhadāraṇyaka says that this veil is like a sheath which covers the entire sword within (1.4.7). Gīta says in verse 7.13 that because of the three Guṇas, people are deluded and are unable to comprehend the imperishable power of Ātmā. Being the ultimate principle of existence, Ātmā is the source and sustainer of all that exists including time, nature, etc. It is therefore stated that Ātmā encompasses and superintends all these causes.

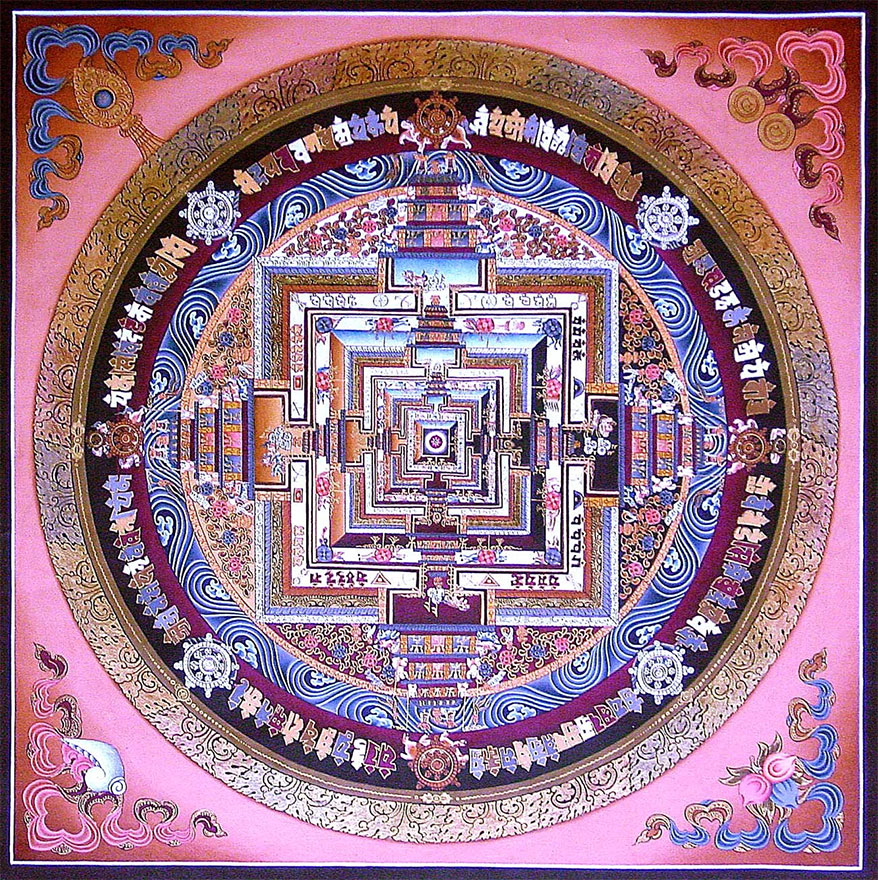

In the next two verses, an ever-moving wheel is introduced; it is called Brahmacakra (ब्रह्मचक्र). This wheel consists of all that exists as the manifested phenomenal universe which is subject to continuous changes featuring manifold characteristics and attributes. The wheel is said to be spinning because of these continuous changes including expansion or contraction. This may be rightly presumed as the aggregate of all the existing galaxies. Ātmā is the impelling force in this wheel. Verse 1.6 says that by knowing the Ātmā to be distinct from the appearance and by attaining to Him, one becomes immortal. See the verse below:

सर्वाजीवे सर्वसंस्थे बृहन्ते अस्मिन्हंसो भ्राम्यते ब्रह्मचक्रे |

पृथगात्मानं प्रेरितारं च मत्वा जुष्टस्ततस्तेनामृतत्वमेति || 1.6 ||

sarvājīve sarvasaṃsthe bṛhante asminhaṃso bhrāmyate brahmacakre;

pṛthagātmānaṃ preritāraṃ ca matvā juṣṭastatastenāmṛtatvameti. (1.6)

Verse meaning: sarvājīve- providing livelihood (or means of existence) for all; sarvasaṃsthe- omnipresent; bṛhante- infinite; asmin- upon this; haṃsaḥ- individual being; bhrāmyate- is moved around; brahmacakre- in Brahmacakra; pṛthak- to be distinct; ātmānaṃ- Ātmā; preritāraṃ- driving force; ca- and; matvā- having known; juṣṭaḥ-attained; tataḥ- thereupon; tena- by that; āmṛtatvameti- become immortal.

Verse meaning: Every individual being is moved around in this omnipresent, infinite Brahmacakra which supports the existence of all. By knowing Ātmā to be distinct from and as the driving force of this Brahmacakra and by attaining to it, one becomes immortal.

Brahmacakra indicates Brahma differentiated into forms and names, as per descriptions already given. We know that Ātmā is the force behind this differentiation (Muṇḍaka 1.1.8 & 1.1.9). This verse says that by so distinguishing the Ātmā as distinct from the differentiated Brahma and by attaining to Him, one becomes immortal.

In the ensuing verses, the Upaniṣad describes how Ātmā rules over the dual constituents of Brahma, which we studied in Bṛhadāraṇyaka 2.3.1 to be the perceptible and imperceptible, mortal and immortal, etc. Let us first see verse 1.8.

संयुक्तमेतत् क्षरमक्षरं च व्यक्ताव्यक्तं भरते विश्वमीशः |

अनीशश्चात्मा बध्यते भोक्तृभावात् ज्ञात्वा देवं मुच्यते सर्वपाशैः|| 1.8 ||

saṃyuktametat kṣaramakṣaraṃ ca vyaktāvyaktaṃ bharate viśvamīśaḥ;

anīśaścātmā badhyate bhoktṛbhāvāt jñātvā devaṃ mucyate sarvapāśaiḥ. (1.8)

Word meaning: saṃyuktam- combined; etat- this; kṣaramakṣaraṃ ca – perishable and imperishable; vyaktāvyaktaṃ- perceptible and imperceptible; bharate- supports; viśvam- universe; īśaḥ- Ruler; anīśaścātmā – and on Ātmā not being the Ruler, (when Ātmā is not heeded as the Ruler); badhyate- gets bonded; bhoktṛbhāvāt – due to one’s being assumed as the enjoyer; jñātvā- on knowing; devaṃ- Deva (Ātmā); mucyate- freed; sarvapāśaiḥ- from all bondages.

Verse meaning: This universe is a combination of the perishable and imperishable, of the perceptible and imperceptible; it is supported by the Ruler (Ātmā). When one does not comply with the dictates of Ātmā, he gets bonded due to his being assumed as the enjoyer. On knowing the Ātmā he is freed from all bondages.

The main theme here is the dual nature of the universe, which we are familiar with. The verse also says that when one denies Ātmā as the ruler, he gets bonded. This denial implies that he is without ruler, anīśa. He himself becomes the ruler and the enjoyer. Thus he strays away from the ruling principle of Ātmā and therefore gets bonded; but, a person who does actions in conformity with the principle of Ātmā, does not get bonded like him. Conformity with the principle of Ātmā is what we know as Dharma.

In the next verse, this dual nature is taken to a higher level, explaining the agent who joins them together. It is verily Māyā. This Upaniṣad itself says in verse 4.10 that Māyā is Prakṛti herself. We have already studied that Māyā or Prakṛti is the power of Ātmā for appearing in various forms and names. The two names Māyā and Prakṛti veritably indicate two functions of the same entity, the power of illusion and the ability to express physical energy, respectively. We have already learned about this two-pronged activity of Prakṛti. Let us see what the present verse says.

ज्ञाज्ञौ द्वावजावीशनीशावजा ह्येका भोक्तृभोग्यार्थयुक्ता |

अनन्तश्चात्मा विश्वरूपो ह्यकर्ता त्रयं यदा विन्दते ब्रह्ममेतत् || 1.9 ||

jñājñau dvāvajāvīśanīśāvajā hyekā bhoktṛbhogyārthayuktā;

anantaścātmā viśvarūpo hyakartā trayaṃ yadā vindate brahmametat. (1.9)

Word meaning: jña- the knower; ajña- the known; dvau- two; ajau- (both are) unborn; īśaḥ- ruler; anīśaḥ- the ruled; ajā- (she is) unborn; hi- indeed; ekā- (she is) one; bhoktṛbhogyārthayuktā – (she) who joins the enjoyer and the enjoyed;

anantaḥ- infinite; ca- and; ātmā- Ātmā; viśvarūpaḥ- appearing in all forms; akartā- not active, non-doer; trayaṃ- three; yadā- when; vindate- knows; brahma- Brahma; etat- this.

Verse meaning: The knower and the known, the ruler and the ruled are both unborn. She who joins these two, the enjoyer and the enjoyed, is also unborn. When one knows these three as (constituting) the Brahma, he realises Ātmā to be infinite and inactive and also appearing in all forms.

In this triad, that which is known and that which joins it with the knower are two facets of Prakṛti. The knower is Puruṣa who is Ātmā Himself when Prakṛti is invoked. All these three constitute Ātmā appearing in infinite forms and names; this is what Brahma is, which we have seen repeatedly in other Upaniṣads. In this combination, Ātmā remains inactive, though he presides over all actions. He is the inner urge; but the expression of this urge is done through Prakṛti only. Whatever is expressed through Prakṛti is tinted by its limitations and hues. Those who understand the urge and also the identity of its source are not carried away by the vagaries and temptations of the said expression. Such understanding is called Vidya or knowledge and the absence thereof is Avidya.

The inactivity of Ātmā mentioned in this verse is a recurrent idea in Gīta. In verses 3.27, 13.29, 14.19 and 18.16 it is said that Ātmā is not the doer; Gīta asserts that all actions are done because of the Guṇas of Prakṛti.

In the combination mentioned above, two parts are distinguishable, perishable and imperishable (as already stated in Bṛhadāraṇyaka 2.3.1 also). The mortal part is Prakṛti and the immortal part is Puruṣa; Ātmā is the ruler of both. It is stated in the next verse that, on attaining to him, all illusions by Prakṛti, come to an end. See the verse below:

क्षरं प्रधानममृताक्षरं हरः क्षरात्मानावीशते देव एकः |

तस्याभिध्यानाद्योजनात्तत्त्वभावात् भूयश्चान्ते विश्वमायानिवृत्तिः || 1.10 ||

kṣaraṃ pradhānamamṛtākṣaraṃ haraḥ kṣarātmānāvīśate deva ekaḥ; tasyābhidhyānādyojanāttattvabhāvāt bhūyaścānte viśvamāyānivṛttiḥ. (1.10)

Word meaning: kṣaraṃ- perishable; pradhānam- primary un-evolved matter (this is a reference to Prakṛti since it is the cause of this matter); amṛtākṣaraṃ- imperishable and immortal; haraḥ- one who carries or bears (means Puruṣa who is Ātmā himself); kṣarātmānau- the perishable and the Puruṣa; īśate- rules over; deva- Deva; ekaḥ- one (without a second); tasya- his; abhidhyānāt- by meditation; yojanāt- by merging with; tattvabhāvāt- by true nature; bhūyaḥ- thereafter; ca- and; ante- at the end; viśvamāyānivṛttiḥ- cessation of all illusions.

Verse meaning: Prakṛti is perishable and Puruṣa is imperishable and immortal. The Deva who rules over both of them is only one (without a second). By merging with His true nature through meditation, all illusions cease at the end.

The Deva mentioned here is verily Ātmā. The same idea as in verses 1.9 & 1.10 is explained in verses 1.11 and 1.12 also. Verse 1.13 says that Ātmā exists in beings like fire exists in its source (twin pieces of Araṇi wood) – unperceived, but not absent. Fire appears only when the pieces of wood are struck with each other; like this, Ātmā becomes known when the body is kindled by Praṇava (Om). Suggesting meditation as the method of this kindling, the next verse (1.14) urges to practise this method continuously and perceive the concealed Ātmā.

Verses 1.15 and 1.16 say about the nature and pervasion of this Ātmā. See the verse 1.15 first:

तिलेषु तैलं दधिनीव सर्पिरापः स्रोतःस्वरणीषु चाग्निः |

एवमात्मात्मनि गृह्यतेऽसौ सत्येनैनं तपसा योऽनुपश्यति || 1.15 ||

tileṣu tailaṃ dadhinīva sarpirāpaḥ srotaḥsvaraṇīṣu cāgniḥ;

evamātmātmani gṛhyate’sau satyenainaṃ tapasā yo’nupaśyati. (1.15)

Word meaning: tileṣu- in sesame seeds; tailaṃ- oil; dadhini- in curd; iva- just as, like that; sarpiḥ- butter; āpaḥ- water; srotaḥsu- in spring; araṇīṣu- in pieces of Araṇi wood; ca- and; agniḥ- fire; evam- in this way; ātmā- Ātmā; ātmani- within oneself, in own self; gṛhyate- is grasped; asau- this; satyena tapasā – by sincere tapas (by unflagging dedication and relentless effort); enaṃ- him; yaḥ- who; anupaśyati- reflect upon ….

Verse meaning: Just as oil in sesame seeds, butter in curd, water in spring and fire in pieces of Araṇi wood, this Ātmā remains imperceptible within everything. One who reflects upon Him by sincere tapas (perceives Him as such).

The phrase ‘this Ātmā’ is a reference to what is mentioned in the verses 1.13 & 1.14. It is declared in the next verse that the Ātmā which thus pervades everywhere is the Brahma. See the verse below:

सर्वव्यापिनमात्मानं क्षीरे सर्पिरिवार्पितम् |

आत्मविद्यातपोमूलं तद्ब्रह्मोपनिषत्परं || 1.16 ||

sarvavyāpinamātmānaṃ kṣīre sarpirivārpitam;

ātmavidyātapomūlaṃ tadbrahmopaniṣatparaṃ. (1.16)

Word meaning: sarvavyāpinam- pervading all; ātmānaṃ- Ātmā; kṣīre- in milk; sarpiḥ- butter; iva- like, as; arpitam- infixed; ātmavidyātapomūlaṃ- the basis of Ātmavidyā and tapas (Ātmavidyā is the instruction on Ātmā); tat- (perceive) that (as instructed in verse 1.14); brahmopaniṣatparaṃ – Brahma beyond Upaniṣads (Brahma taught by Upaniṣads).

Verse meaning: Ātmā is pervading all, like butter is infixed in milk and He is the basis of Ātmavidyā and tapas; know that Ātmā to be Brahma taught by Upaniṣads.

Kaṭha Upaniṣad says in 2.15 that the basis of all tapas, study of Vedas and observance of chastity is the syllable ‘Om’, which represents Ātmā. This is what the word ‘ātmavidyātapomūlaṃ’ expresses here. The verse says that Ātmā which pervades everything is Brahma. The clause that qualifies Ātmā here is not a mere adjectival clause, but it states a condition. Its implication is that Ātmā is Brahma when He is in the state of pervading all; when Ātmā remains within Himself, with all the manifestations withdrawn, He is not Brahma. This is what the verse conveys.

Chapter 2 opens with some prescriptions of physical disciplines that may help in attaining to the ultimate principle. These disciplines consist of controlling the mind and senses. Verse 2.14 says that like a mirror with dust shines brilliantly when cleaned, one gets devoid of miseries and becomes fully contented when he knows the ultimate principle.

It is declared in verse 2.15 that like a lamp helps in sighting objects, the principle of Ātmā helps in getting true knowledge of Brahma. When one knows Ātmā as unborn, eternal and free from modifications, he gets relieved from all bondages. Verse 2.16 affirms that Ātmā is all-pervading; He is the manifesting principle and exists in all beings as the subtle entity.

In chapter 3 we see a detailed description on the nature of Ātmā. Verse 3.1 says that those who know the one and only one Ātmā ruling the entire world with His power of Māyā, become immortal; Ātmā is the one from whom, in the beginning, the worlds emerged and to whom, in the end, the worlds will merge. This idea is further discussed in various dimensions in the next few verses and the discussion concludes in verses 3.9 and 3.10. We may consider these verses now.

यस्मात्परं नापरमस्ति किंचित् यस्मान्नाणीयो न ज्यायोऽस्ति कश्चित् |

वृक्ष इव स्तब्धो दिवि तिष्ठत्येकः तेनेदं पूर्णं पुरुषेण सर्वम् || 3.9 ||

yasmātparaṃ nāparamasti kiṃcit yasmānnāṇīyo na jyāyo’sti kaścit;

vṛkṣa iva stabdho divi tiṣṭhatyekaḥ tenedaṃ pūrṇaṃ puruṣeṇa sarvam. (3.9)

Word meaning: yasmāt- than whom; paraṃ- beyond; na- not; aparam- any other; asti- exists; kiṃcit- anything; aṇīyaḥ- subtler; jyāyaḥ- grosser; kaścit- anyone;

vṛkṣa- tree; iva- just as; stabdhaḥ- unmoving; divi- in resplendence; tiṣṭhati- dwells; ekaḥ- only one; tena- by Him; idaṃ- this, here; pūrṇaṃ- full; puruṣeṇa- by Puruṣa; sarvam- all.

Verse meaning: All this (the entire universe) is full with the one and only one Puruṣa who dwells in resplendence and is unmoving like a tree; there is nothing beyond him and none subtler or grosser than him.

We already know that Puruṣa is Ātmā with Prakṛti invoked. The phrase ‘dwells in resplendence’ means that Puruṣa is pure resplendence. He is unmoving since he fills everywhere; no space is left for him to move about. Regarding subtlety and grossness we have already discussed them in Chāndogya 3.14.2 & 3.14.3, Kaṭha 2.20 and Muṇḍaka 3.1.7.

Now we may see verse 3.10. It says that those who know the said Puruṣa become immortal, while others get grieved.

ततो यदुत्तरतरं तदरूपमनामयम् |

य एतद्विदुरमृतास्ते भवन्ति अथेतरे दुःखमेवापियन्ति || 3.10 ||

tato yaduttarataraṃ tadarūpamanāmayam;

ya etadviduramṛtāste bhavanti athetare duḥkhamevāpiyanti. (3.10)

Word meaning: tataḥ- than that (than the visible universe referred to in the previous verse); yat- what, that which; uttarataraṃ- far higher; tat- that; arūpam- formless; anāmayam- free from afflictions; yaḥ- who; etat- this; viduḥ- know; amṛtāḥ- immortal; te- they; bhavanti- become; atha- but; itare- the others; duḥkham- misery; eva- indeed, only; apiyanti- go into, suffer.

Verse meaning: That which is far higher than the visible universe is formless and free from afflictions. Those who know this become immortal and others suffer misery.

The reference here is obviously to Puruṣa who is Ātmā. It is a sustained message in Upaniṣads that knowledge of Ātmā leads to immortality. The phrase ‘far higher than’ indicates subtlety.

In the next three verses, the Upaniṣad elaborates on the pervasion of Puruṣa in universe. It is said that Puruṣa dwells in the inner-most part of beings sustaining them all. He is said to be of thumb-size; this is a reference to the Heart (Thalamus), the centre of consciousness within the body, the size of which approximates to thumb. It is also reiterated that those who know him become immortal.

The next two verses (3.14 and 3.15) are the first two hymns of Puruṣa Sukta of Ṛgveda (10.90). The importance of Puruṣa Sukta is that it contains some sparks of the basic thoughts constituting the foundation on which spiritual philosophy of India evolved in course of later ages. Ṛsi Narāyaṇa is its revealer and Puruṣa is the Devatā. See the verses below:

सहस्रशीर्षा पुरुषः सहस्राक्षः सहस्रपात् |

स भूमिं विश्वतो वृत्वा अत्यतिष्ठद्दशाङ्गुलम् || 3.14 ||

sahasraśīrṣā puruṣaḥ sahasrākṣaḥ sahasrapāt;

sa bhūmiṃ viśvato vṛtvā atyatiṭhaddaśāṅgulam. (3.14)

Word meaning: sahasraśīrṣā- with thousand heads; puruṣaḥ- Puruṣa; sahasrākṣaḥ- with thousand eyes; sahasrapāt- with thousand feet; saḥ- He; bhūmiṃ- the world; viśvato- from all sides; vṛtvā- having enveloped; atyatiṣṭhat- extends by, transcends; daśāṅgulam- by ten fingers.

Verse meaning: The Puruṣa is with thousand heads, thousand eyes and thousand feet. Having enveloped the world from all sides He extends further by ten fingers.

The word ‘thousand’ indicates innumerability; the reference of thousand heads, eyes and feet is an allusion to the all-pervasive nature of Puruṣa. Extending by ten fingers means that Puruṣa is not contained within the world, but the world is located within Him; He holds the world. Gīta 9.4 declares thus: ‘all beings abide in Me: and I do not dwell in them’. Gīta further says in 9.5 thus: ‘I hold the beings and I am not within them’.

पुरुष एवेदं सर्वं यद्भूतं यच्च भव्यम् |

उतामृतत्वस्येशानो यदन्नेनातिरोहति || 3.15 ||

puruṣa evedaṃ sarvaṃ yadbhūtaṃ yacca bhavyam;

utāmṛtatvasyeśāno yadannenātirohati. (3.15)

Word meaning: puruṣa- Puruṣa; eva- indeed, certainly; idaṃ sarvaṃ – this all; yadbhūtaṃ- that which existed in the past; yacca bhavyam – and that which will come to exist in future; uta- and; amṛtatvasyeśāno- dispenser of immortality, the sustainer; yadannenātirohati – that which grows by food (living beings).

Verse meaning: Puruṣa indeed is all that exists at present, that existed in the past and that will exist in future; He is the dispenser of immortality to all that grows by food.

Dispenser of immortality means the provider of the immortal part of beings. We know that all beings have a mortal part and an immortal part; for, Brahma has two forms (Bṛhadāraṇyaka 2.3.1) and therefore, beings originated by its expansion also must have two forms, namely mortal and immortal. The mortal part comes from Prakṛti and the immortal part from Puruṣa. This is the idea.

The next two verses are explanations to the Vedic hymns quoted above. Verse 3.16 says that Puruṣa has hands, feet, eyes, heads, mouths and ears everywhere; He exists enclosing everything. This verse is same as verse 13.13 of Gīta. Verse 3.17 also is seen partially reproduced in Gīta as verse 13.14. It says that He is without senses, but He is the light of all senses; He is the Ruler and refuge of all. Combining these two verses together, we have to understand that Puruṣa is inherently devoid of senses and other organs, but he possesses all the organs of all the beings belonging to the manifestation.

In continuation of the above idea, the next verse asserts the greatness of Puruṣa in precise terms. See the verse below:

अपाणिपादो जवनो ग्रहीता पश्यत्यचक्षुः स शृणोत्यकर्णः |

स वेत्ति वेद्यं न च तस्यास्ति वेत्ता तमाहुरग्र्यं पुरुषं महान्तम् || 3.19 ||

apāṇipādo javano grahītā paśyatyacakṣuḥ sa śṛṇotyakarṇaḥ;

sa vetti vedyaṃ na ca tasyāsti vettā tamāhuragryaṃ puruṣaṃ mahāntam. (3.19)

Word meaning: apāṇipādaḥ- without hands and feet; javanaḥ- moving quickly; grahītā- grasping; paśyati- sees; acakṣuḥ- without eyes; saḥ- He; śṛṇoti- hears; akarṇaḥ- without ears; vetti- knows; vedyaṃ- that which is to be known; na- not; ca- and; tasya- His; asti- exists; vettā- knower; tamāhuragryaṃ – He is said to be primal; puruṣaṃ- Puruṣa; mahāntam- great.

Verse meaning: He moves quickly without feet, grasps without hands, sees without eyes and hears without ears. He knows all that is to be known; but, there is none who knows Him. He is said to be the great primal Puruṣa.

The verse implies that Puruṣa is the facilitator of all the actions done with the ten senses; all those actions become possible because of Him only.

The next verse (3.20) is same as verse 2.20 of Kaṭha, except a minor difference in arrangement of words. The verse says about subtlety and grossness of Puruṣa, which we have seen many a time.

The fourth chapter discourses on the manifestation and pervasion of Puruṣa. The first verse therein says that Puruṣa, who is One without a second and devoid of ‘covering’ (envelop), projects many coverings out of unknown intentions. The word used here to mean ‘covering’ is varṇa (वर्ण) which has got many meanings like colour, type, etc. Here, the context takes the meaning, ‘covering’; for, manifestations are like coverings (envelopes) of Puruṣa. His original state is devoid of coverings.

In the next few verses, Puruṣa is described as the ruling force of the entire universe. Then, in verses 4.6 and 4.7, the two roles of Puruṣa in every being are presented by means of an allegory of two birds, which we have studied in great detail in verses 3.1.1 and 3.1.2 of Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad.

Turning to verse 4.10 we find an important declaration which is not seen in any Principal Upaniṣad. Here is the verse:

मायां तु प्रकृतिं विद्यात् मायिनं तु महेश्वरम् |

तस्यावयव भूतैस्तु व्याप्तं सर्वमिदं जगत् || 4.10 ||

māyāṃ tu prakṛtiṃ vidyāt māyinaṃ tu maheśvaram;

tasyāvayava bhūtaistu vyāptaṃ sarvamidaṃ jagat. (4.10)

Word meaning: māyāṃ- Māyā (illusion); tu- (an expletive); prakṛtiṃ- Prakṛti; vidyāt- know; māyinaṃ- the Lord of Māyā (Illusionist); maheśvaram- the Great Īśa (Puruṣa);

tasya- His; avayava- body parts; bhūtaiḥ- by beings; vyāptaṃ- filled; sarvamidaṃ jagat – all this world.

Verse meaning: Know that Māyā is Prakṛti and the Lord of Māyā is Puruṣa. The entire world is filled by beings which are His body parts.

This verse declares that Māyā and Prakṛti are same; the difference in names indicates only the diverse functions. As already mentioned above, Māyā causes illusion and Prakṛti provides the material for it. Both these functions are done by the same power of Ātmā that is used to appear variously.

The main message in the verses that follow is that by knowing Puruṣa, one gets immortality; nature of Puruṣa is also dealt with in them. It is stated in these verses that Puruṣa is the entity from whom the universe emerges and to whom it merges; He is the origin of all Devas; He encompasses the entire universe; He dwells in the Hearts of beings; He bestows the knowing power (Prañā – प्रज्ञा); His name is great glory; He has no creator; and He is not perceivable by the senses. These are all characteristics which we have already studied in other Upaniṣads and therefore, no detailed study is warranted here.

Now we move on to chapter 5. The subject of discussion therein is how Ātmā projects beings and how He sustains and withdraws them. In verse 5.1 a new concept is introduced connecting Vidyā (knowledge – enlightenment) and Avidyā (ignorance) with immortality and mortality respectively. The verse is given below:

द्वे अक्षरे ब्रह्मपरे त्वनन्ते विद्याविद्ये निहिते यत्र गूढे |

क्षरं त्वविद्या ह्यमृतं तु विद्या विद्याविद्ये ईशते यस्तु सोऽन्यः || 5.1 ||

dve akṣare brahmapare tvanante vidyāvidye nihite yatra gūḍhe;

kṣaraṃ tvavidyā hyamṛtaṃ tu vidyā vidyāvidye īśate yastu so’nyaḥ. (5.1)

Word meaning: dve- two, both; akṣare- in immortal; brahmapare- in Brahmapara, in the subtlety of Brahma; anante- in the infinite; vidyāvidye- Vidyā and Avidyā; nihite- lie deposited or hidden; yatra- where; gūḍhe- secretly; kṣaraṃ- mortal, perishable; tu- but; avidyā- Avidyā; hi-indeed; amṛtaṃ- immortal; vidyā- Vidyā; īśate- rules; yaḥ- who; saḥ- He; anyaḥ- another, different person.

Verse meaning: Both Vidyā and Avidyā lie hidden secretly in the immortal, infinite, subtle Brahma. Of these, Avidyā is mortal and Vidyā is immortal. But, the One who rules over both is another (different from both).

Vidyā implies knowledge of the supreme principle, the Ātmā. We know from many declarations of the Upaniṣads, already studied by us, that this knowledge leads to immortality. We have had sufficient discussions on immortality too. Avidyā is the opposite of Vidyā and therefore it obviously implies absence of the knowledge of Ātmā. This verse says that both of them are hidden in the subtlety of Brahma; subtlety denotes the undifferentiated state of Brahma. We know that mortality and immortality are two facets of Brahma (vide Bṛhadāraṇyaka 2.3.1). The verse here further says that He who rules over both is entirely different from them. He is the One who rules over the whole of Brahma; He is Ātmā.

In the next three verses the Upaniṣad reiterates that Puruṣa superintends all sources of birth and all forms of beings; He projects and withdraws beings again and again and through that process exercises full control over them.

Verses 5.5 and 5.6 examine the relation between Ātmā and Brahma. Let us consider them together.

यच्च स्वभावं पचति विश्वयोनिः पाच्यांश्च सर्वान् परिणामयेद्यः |

सर्वमेतद्विश्वमधितिष्ठत्येको गुणांश्च सर्वान् विनियोजयेद्यः || 5.5

yacca svabhāvaṃ pacati viśvayoniḥ pācyāṃśca sarvān pariṇāmayedyaḥ; sarvametadviśvamadhitiṣṭhatyeko guṇāṃśca sarvān viniyojayedyaḥ. (5.5)

Word meaning: yat- which; ca- and; svabhāvaṃ- inherent nature; pacati- makes evident, manifest; viśvayoniḥ- the source of universe; pācyān- those made evident; sarvān- all; pariṇāmayet- bring to an end; yaḥ- who; sarvametadviśvam- all this world; adhitiṣṭhati- superintends; ekaḥ- the One; guṇān- Guṇas; sarvān- all; viniyojayet- employ.

तद्वेदगुह्योपनिषत्सु गूढं तद्ब्रह्मा वेदते ब्रह्मयोनिम् |

ये पूर्वं देवा ऋषयश्च तद्विदुः ते तन्मया अमृता वै बभूवुः || 5.6 ||

tadvedaguhyopaniṣatsu gūḍhaṃ tadbrahmā vedate brahmayonim;

ye pūrvaṃ devā ṛṣayaśca tadviduḥ te tanmayā amṛtā vai babhūvuḥ. (5.6)

Word meaning: tat- that; vedaguhyopaniṣatsu- in the Upaniṣads which are the essence of Vedas; gūḍhaṃ- hidden; brahmā- the Lord Brahmā; vedate- knows; brahmayonim- source of Brahma; ye- who; pūrvaṃ- in the past; devāḥ- Devas; ṛṣayaḥ- Ṛsis; tat- that viduḥ- knew; te- they; tanmayā- absorbed in it; amṛtā- immortal; vai- verily, indeed; babhūvuḥ- became.

Verse meaning (of both the verses): That One who, being the source of the universe, manifests (his own) inherent nature and (in due course) withdraws all those thus manifested; who is the only One superintending the whole world; and who employs the Guṇas (for manifestation) – He is the hidden principle in Upaniṣads which are the essence of Vedas. Lord Brahmā knows Him to be the source of Brahma. Those Devas and Ṛsis who knew Him in the past verily became immortal.

In the first of the two verses, the nature of the entity is described variously (i) as the source of the universe, (ii) as the principle that manifests himself and later withdraws all that is so manifested, (iii) as the only One who superintends the whole world, and (iv) as the Ruler who employs Guṇas (for manifestation). In the second, it is said that Brahma originated from Him. All these are known facts for us. It is said here that Lord Brahmā knew Him to be the source of Brahma. Lord Brahmā is renowned as the Lord of speech (Vāgīśa) and therefore, He is mentioned to add credibility to the declaration.

We see two other outstanding declarations in verses 5.10 and 5.14; they are not seen in any Principal Upaniṣad. Let us first see verse 5.10.

नैव स्त्री न पुमानेष न चैवायं नपुंसकः |

यद्यच्छरीरमादत्ते तेन तेन स युज्यते || 5.10 ||

naiva strī na pumāneṣa na caivāyaṃ napuṃsakaḥ;

yadyaccharīramādatte tena tena sa yujyate. (5.10)

Word meaning: naiva strī – na eva strī – neither female; na pumān – nor male; eṣa- He; na caivāyaṃ napuṃsakaḥ – He is not neuter either; yadyat- whatever; śarīram- body; ādatte- assumes; tena tena – with each one of that; sa- He; yujyate- be identified accordingly.

Verse meaning: He is neither female, nor male; He is not neuter either. Whatever body is assumed, He becomes identified with it accordingly.

The declaration is important in that it categorically asserts Ātmā to be genderless. Now, we shall see verse 5.14:

भावग्राह्यमनीडाख्यं भावाभावकरं शिवम् |

कलासर्गकरं देवं ये विदुस्ते जहुस्तनुम् || 5.14 ||

bhāvagrāhyamanīḍākhyaṃ bhāvābhāvakaraṃ śivam;

kalāsargakaraṃ devaṃ ye viduste jahustanum. (5.14)

Word meaning: bhāvagrāhyam- conceived by the Heart; anīḍākhyaṃ- known to be incorporeal; bhāvābhāvakaraṃ- projecting and withdrawing; śivam- blissful;

kalāsargakaraṃ- integrating and disintegrating; devaṃ- Deva (Ātmā); ye- who; viduḥ- know; te- they; jahuḥ- give up; tanum- body, body consciousness.

Verse meaning: Ātmā can be conceived only by the Heart; He is known to be incorporeal; He projects and withdraws (beings); He integrates parts (to project beings) and disintegrates them; and He is blissful. Those who know Him give up body consciousness.

The verse says about giving up body. This does not mean committing suicide; it indicates only the giving up of body consciousness. This in turn implies relief from all bondages; it is mokṣa or perfect freedom. Such a person never gets affected by worldly concerns and never capitulates to Kāma. So, on knowing Ātmā one gets mokṣa and he becomes immortal too.

Chapter 6 deals with the supremacy and uniqueness of Ātmā. The verses in the chapter describe Ātmā as the One without a second who projects, sustains and withdraws the phenomenal world. We however concentrate on those verses which possess comparatively higher philosophical importance and on those which are generally believed to be very difficult to understand. Let us begin with verse 1.

स्वभावमेके कवयो वदन्ति कालं तथान्ये परिमुह्यमानाः |

देवस्येष महिमा तु लोके येनेदं भ्राम्यते ब्रह्मचक्रम् || 6.1 ||

svabhāvameke kavayo vadanti kālaṃ tathānye parimuhyamānāḥ;

devasyeṣa mahimā tu loke yenedaṃ bhrāmyate brahmacakram. (6.1)

Word meaning: svabhāvam- nature; eke- some; kavayo- scholars; vadanti- say; kālaṃ- Time; tathā- thus; anye- others; parimuhyamānāḥ- confused; devasya- of the Deva; eṣa- this; mahimā- power of manifestation (power to appear variously at will); tu- but; loke- in the world; yena- by whom; idaṃ- this; bhrāmyate- revolves; brahmacakram- Wheel of Brahma.

Verse meaning: Some scholars say that the Wheel of Brahma revolves because of its own nature, but some others say that it is because of Time. Both are confused. What we see in the world is the power of Deva (Puruṣa – Ātmā) to appear variously; the Wheel of Brahma revolves because of this power.

We have discussed about the Wheel of Brahma in the introduction to verse 1.6. Further details can be seen in the study of verse 1.6 itself. The message here is that the phenomenal world does not exist on its own. There is a subtle transcending power which is the energy behind it. Kaṭha 2.6 declares that those, who see nothing beyond the phenomenal world, are susceptible to recurring miseries.

Verse 6.2 clarifies the contention in 6.1 by elaborating the concept. See the verse below:

येनावृतं नित्यमिदं हि सर्वं ज्ञः कालकारो गुणी सर्वविद्यः |

तेनेशितं कर्म विवर्तते ह पृथिव्यप्तेप्तेजोऽनिलखानि चिन्त्यम् || 6.2 ||

yenāvṛtaṃ nityamidaṃ hi sarvaṃ jñaḥ kālakāro guṇī sarvavidyaḥ;

teneśitaṃ karma vivartate ha pṛthivyaptejo’nilakhāni cintyam. (6.2)

Word meaning: yena- by whom; āvṛtaṃ- enveloped; nityam- for ever; idaṃ- this; hi- indeed; sarvaṃ- all; jñaḥ- the knowing entity; kālakāraḥ- the initiator of time; guṇī- the Lord of Guṇas; sarvavid- omniscient; yaḥ- who; tena- by Him; īśitaṃ- ruled; karma- Karma; (tena- by Him); vivartate- come forth; ha- indeed; pṛthivyaptejo’nilakhāni- earth, water, fire, air and space (Pañcabhūtas); cintyam- to be conceived.

Verse meaning: It is because of the omniscient and knowing entity, the initiator of time and the Lord of Guṇas, that Karma gets actualised and Pañcabhūtas emerge; this is to be borne in mind.

The reference of ‘omniscient’, etc. obviously relates to Ātmā. This verse says that Ātmā is instrumental in the performance of Karma and that He stimulates the emergence of Pañcabhūtas. Therefore the Wheel of Brahma evidently revolves by this power.

The next two verses say about the connection between time and the continued existence of manifestation and why Ātmā is not affected by Karmas. Incidentally, these two verses are considered to be a hard nut for interpreters. Let us therefore approach them with caution. The two verses are connected with each other and therefore we are to consider them together.

तत्कर्म कृत्वा विनिवर्त्य भूयः तत्त्वस्य तत्त्वेन समेत्य योगम् |

एकेन द्वाभ्यां त्रिभिरष्टभिर्वा कालेन चैवात्मगुणैश्च सूक्ष्मैः || 6.3 ||

tatkarma kṛtvā vinivartya bhūyaḥ tattvasya tattvena sametya yogam;

ekena dvābhyāṃ tribhiraṣṭabhirvā kālena caivātmaguṇaiśca sūkṣmaiḥ. (6.3)

Word meaning: tat- that; karma- Karma; kṛtvā- having done; vinivartya- ceasing, taking a break; bhūyaḥ- again; tattvasya- to the element (to each of the Pañcabhūtas); tattvena- by the element; sametya yogam – joining together; ekena dvābhyāṃ tribhiraṣṭabhirvā- by one, twos or by threes and eights; kālena- by time; caiva- and surely; ātmaguṇaiśca sūkṣmaiḥ – by own subtle Guṇas.

आरभ्य कर्माणि गुणान्वितानि भावांश्च सर्वान्विनियोजयेद्यः |

तेषामभावे कृतकर्मनाशः कर्मक्षये याति स तत्त्वतोऽन्यः || 6.4 ||

ārabhya karmāṇi guṇānvitāni bhāvāṃśca sarvānviniyojayedyaḥ;

teṣāmabhāve kṛtakarmanāśaḥ karmakṣaye yāti sa tattvato’nyaḥ. (6.4)

Word meaning: ārabhya- having begun; karmāṇi- Karmas; guṇānvitāni- with Guṇas; bhāvān- various mental states of beings; ca- and; sarvān- all (beings); viniyojayet- assign to or employ; yaḥ- who; teṣāmabhāve- in the absence of or being devoid of them (the bhāvāḥ); kṛtakarmanāśaḥ- dissolution of performed karma; karmakṣaye- on dissolution of karma; yāti- proceed to be, achieve; sa- He; tattvato’nyaḥ- different from tattva (from element).

Verse meaning (both verses together): Having done that Karma (the projection of Pañcabhūtas) He effects a pause; then He joins together elements with elements by employing their own subtle Guṇas and by connecting time in ones, twos, or threes and eights.

Having thus initiated Karmas employing Guṇas, He assigns various bhāvās to all beings. Being devoid of such bhāvās, all these Karmas performed by Him stand dissolved (He is not affected by them). As such, He remains in the state of being different from tattva (different from elements).

The first verse (6.3) says about the mode of projection of the phenomenal world. This takes place in two stages. The initial stage is projection of Pañcabhūtas. There is a break after the first stage; this implies that projection of new elements is discontinued. The second stage is projection of beings from Pañcabhūtas by their combination on the basis of subtle Guṇas and by linking with time. The measure of time is given here as one, two, or threes and eights. All are to be understood as units of time. One refers to one day or its multiples; ‘two’ refers to day and night; threes and eights are references to eight divisions of a day consisting of three hours each (Prahara or प्रहर is the name of each such division of time with a duration of three hours; that is why 3 x 8).

Verse 2.4.12 of Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad states that Pañcabhūtas are verily vijñānaghana (विज्ञानघन – mass of knowledge); it also states that all beings originate from them and on expiry of a given time merge into them. This revelation matches well with the teaching in verse 6.3 here.

The emergence of beings from Pañcabhūtas is by employing Guṇas and invoking time. According to the second verse (6.4), by initiating the emergence of beings the Puruṣa or Ātmā assigns bhāvās to beings. This simply means that with the assumption of bodies made of Pañcabhūtas, beings assume bhāvās on account thereof. Bhāvās are, as we have seen above, mental states of beings, the basis of which is the ‘I’ and ‘Mine’ consciousness. It is these bhāvās which cause attachment and bondage. In the absence of such bhāvās, the performed Karmas are incapable of causing attachment and bondage; this is mentioned in the verse as dissolution of Karmas. Since Puruṣa has no such bhāva, He is described in the verse to be different from or beyond the basic elements of projection of beings, the Pañcabhūtas.

In the next three verses, the Upaniṣad urges to realise the said Ātmā by constant meditation. Verses 8 and 9 contain an important declaration which is the leading theme of spiritual knowledge in some other religion originated outside India. Let us look at the verses one by one.

न तस्य कार्यं करणं च विद्यते न तत्समश्चाभ्यधिकश्च दृश्यते |

परास्य शक्तिर्विविधैव श्रूयते स्वाभाविकी ज्ञानबलक्रिया च || 6.8 ||

na tasya kāryaṃ karaṇaṃ ca vidyate na tatsamaścābhyadhikaśca dṛśyate;

parāsya śaktirvividhaiva śrūyate svābhāvikī jñānabalakriyā ca. (6.8)

Word meaning: na- not; tasya- His; kāryaṃ- to be done; karaṇaṃ- doing, activity; ca- and; vidyate- exist; tatsamaḥ- His equal; abhyadhikaḥ- superior; na dṛśyate- not seen, does not exist; asya- His; parāśaktiḥ- great power; vividhā- various; eva- surely; śrūyate- heard; svābhāvikī- natural, inherent; jñānabala- strength of knowledge; kriyā- composition.

Verse meaning: There exists nothing for Him to do; nor does He have any activity. None is equal or superior to Him. What is declared (in Vedas and all) is only about the various expressions of his great power and also about the strength and composition of his inherent knowledge.

The ‘He’ mentioned here is the ‘Lord of all lords, the God of all gods and the Ruler of all rulers’ (vide verse 6.7). The declaration about Him here is that none is equal or superior to Him, which is the key word of some other religious philosophy. This very same philosophy has been an established thought all through the spiritual literature of India, especially in the higher texts of Upaniṣad which originated in this land in very ancient times when the whole world was tottering with infantile conceptions. This verily is the message conveyed by the declarations in Upaniṣads about Ātmā being one without a second, His pervading the world, His being the origin and support of all, His being not surpassable, etc.; we have studied them all. Gīta says in verse 7.7 that there is nothing superior to Kṛṣṇa who is Ātmā. Apart from stating categorically that the Supreme God has no equal or superior, the Upaniṣads further declare that this God is simply a principle, Ātmā who is without body and who pervades all.

Regarding the absence of actions, Gīta says in verse 3.22 that no duty exists anywhere for Kṛṣṇa to do and nothing is there for Him to achieve. If He is still engaged in duties, it is because of His being currently in a human body.

Now see verse 6.9 below:

न तस्य कश्चित् पतिरस्ति लोके न चेशिता नैव च तस्य लिङ्गम् |

स कारणं करणाधिपाधिपो न चास्य कश्चित् जनिता न चाधिपः || 6.9 ||

na tasya kaścit patirasti loke na ceśitā naiva ca tasya liṅgam;

sa kāraṇaṃ karaṇādhipādhipo na cāsya kaścit janitā na cādhipaḥ. (6.9)

Word meaning: na- not; tasya- His; kaścit- anyone; patiḥ- master; asti-exists; loke- in the world; ca- and; īśitā- superior; naiva- nor even; liṅgam- sign, idol; sa- He; kāraṇaṃ- cause; karaṇādhipādhipaḥ- master of the mind (mind being the master of karaṇās, the organs of action); asya- His; janitā- originator; adhipaḥ- lord.

Verse meaning: He has no master in the world; nor any superior or idol. He is the cause (of all) and master of the mind; He has no father (originator) or lord.

Put in purely theological terms, this verse means that God has no father and no idol. He is without origin and is the Supreme Ruler of the world. This God, according to the previous verses, is the Lord of all lords; He is Ātmā.

Thus, the superiority and unity of Ātmā, the Supreme God who is only a bodiless principle, is unequivocally and unambiguously asserted in these two verses. But, in spite of being the land of origin of this supreme thought, that too, hundreds of years before the whole world had any glimpse of anything like it, India, as a people, has not lived up to that greatness, but instead, chose to continue with the primitive practices of yore in the name of religion. It is a matter of great pity that darkness is preferred to sublime light and mythology to rational philosophy. If religion is anything concerned with the practice of spiritual principles, its ultimate is the religion of Upaniṣads. But, in this land of Upaniṣads, even after thousands of years since the culminating thoughts of rational spiritual philosophy were revealed, the religion of Upaniṣads still remains a mere ideal. Upaniṣads contain the ultimate of spiritual philosophy beyond which no speculative enterprise can ever go. Indians are not utilising the strength of this supreme philosophy, even to a small extent. Resultantly, they remain vulnerable to the attacks of external ideals with lesser philosophic merit.

The message in the above two verses is taken further to new heights in the ensuing verses. See below verse 6.11.

एको देवः सर्वभूतेषु गूढः सर्वव्यापी सर्वभूतान्तरात्मा |

कर्माध्यक्षः सर्वभूताधिवासः साक्षी चेता केवलो निर्गुणश्च || 6.11 ||

eko devaḥ sarvabhūteṣu gūḍhaḥ sarvavyāpī sarvabhūtāntarātmā;

karmādhyakṣaḥ sarvabhūtādhivāsaḥ sākṣī cetā kevalo nirguṇaśca. (6.11)

Word meaning: ekaḥ- the one without a second; devaḥ- Deva; sarvabhūteṣu- in all beings; gūḍhaḥ- hidden; sarvavyāpī- all-pervading; sarvabhūtāntarātmā- the Ātmā within all beings; karmādhyakṣaḥ- the one who presides over all Karma, the impeller of Karma; sarvabhūtādhivāsaḥ- the abode of all beings; sākṣī- witness; cetā- consciousness; kevalaḥ- absolute; nirguṇaḥ- devoid of Guṇas; ca- and.

Verse meaning: There is only one Deva; He is the Ātmā within all; He is hidden in all beings, pervading them, impelling and witnessing all their Karma; He is the abode of all beings, pure consciousness and the absolute; He is also devoid of Guṇas.

This is the paramount revelation of Indian spiritual philosophy. The Deva or Īśwara or God is only one and He is the Ātmā within all. He is revealed as pure consciousness and the absolute. The phrase ‘hidden in all beings’ indicates the impossibility of grasping Him by the sense organs as well as His pervasion. Gīta verse 18.61 also declares that Īśwara is within everyone’s Heart. So, one need not look outwards in search of Īśwara; He is in every iota of all. As such, those who are in search of Īśwara should look inwards; all prayers are to be directed inwards. Prayers are nothing but intense willing; their fulfilment is determined by the intensity and perseverance with which they are made. We studied about it in the Science of Praśna Upaniṣad (verse 3.10).

We know that Ātmā is SAT-CHIT-ĀNANDA and also that all Karmas of all beings result from the urge either to exist, or to know and express, or to derive happiness. These three urges originate directly from SAT, CHIT, and ĀNANDA respectively. It is because of this fact that Ātmā is stated as the impeller of Karma. Since He is without any organs of actions and He has nothing to be achieved, no action is executed by Him; he is said to be a witness only. He is without Guṇa since Prakṛti is the repository of Guṇas. Verse 6.11 thus encompasses all important features of what we understand as Ātmā and also states that this Ātmā is the Īśwara or God.

In the next verse, the Deva is said to be the one who controls the multitude of beings which are inherently incapable of self-movement. As stated above, it is the urge derived from Ātmā that makes the beings act in various ways; this is the way Ātmā controls all. The verse also says that Ātmā makes a single seed manifest as many; the seed is Himself and by invoking the manifesting power, the Prakṛti, He makes Himself many. Verses 6.12 and 6.13 declare that those who know Ātmā attain eternal bliss.

Verse 6.14 states that Ātmā is the only shining light and all beings shine because of His light. We saw the same verse in Kaṭha 5.15 and Muṇḍaka 2.2.10.

Another important declaration comes in verses 6.18 and 6.19. It asserts that Brahma was projected by Ātmā in the beginning.

यो ब्रह्माणं विदधाति पूर्वं यो वै वेदांश्च प्रहिणोति तस्मै |

तं ह देवमात्मबुद्धिप्रकाशं मुमुक्षुर्वै शरणमहं प्रपद्ये || 6.18 ||

yo brahmāṇaṃ vidadhāti pūrvaṃ yo vai vedāṃśca prahiṇoti tasmai;

taṃ ha devamātmabuddhiprakāśaṃ mumukṣurvai śaraṇamahaṃ prapadye. (6.18)

Word meaning: yaḥ- who; brahmāṇaṃ vidadhāti – projected Brahma; pūrvaṃ- previously, in the past; vai- indeed; vedān prahiṇoti – revealed Vedas; tasmai- to it;

Taṃ devam- in that Deva; ha- indeed; ātmabuddhiprakāśaṃ- brightening one’s buddhi; mumukṣuḥ- desirous of freedom from bondages; vai- indeed; ahaṃ – I; śaraṇam prapadye- seek refuge.

Verse meaning: Being desirous of freeing myself from worldly bondages, I seek refuge in that Deva who brightens up my Buddhi and who projected Brahma in the past and revealed Vedas to it.

The message of the verse is that those who realise Ātmā become free from bondages. Conversely, those, who eliminate all the bondages from inside, realise Ātmā. We have seen this message again and again previously. Two things specially mentioned in the verse are the brightening of Buddhi and projection of Brahma. It is consciousness that makes Buddhi shine; consciousness is a constituent of Ātmā and therefore brightening of Buddhi is truly done by Ātmā. When Ātmā invokes its power Prakṛti, He is known as Puruṣa; we know that this Prakṛti-Puruṣa combine is Brahma. So Brahma is verily projected by Ātmā. Brahma on expansion appears as the phenomenal world. The Vedas occurred to the meditative minds of the world, in the past. This is what the verse describes as revealing the Vedas to Brahma.

Verse 6.19 is a description of various characteristics of Ātmā. It is stated that Ātmā is without parts and activity, faultless, untainted, etc. He is like a mighty fire that burnt down all fuel and He is the supreme link that connects one to immortality. In the reference of ‘mighty fire burning all fuel’ the fire is pure knowledge and fuel is the world of sensual experiences. The implication is that pure knowledge burns down all attachments to the sensual world.

The next verse (6.20) declares in definite terms that without knowing Ātmā there cannot be any relief from misery.

यदा चर्मवदाकाशं वेष्टयिष्यन्ति मानवाः |

तदा देवमविज्ञाय दुःखस्यान्तो भविष्यति || 6.20 ||

yadā carmavadākāśaṃ veṣṭayiṣyanti mānavāḥ;

tadā devamavijñāya duḥkhasyānto bhaviṣyati. (6.20)

Word meaning: yadā- when; carmavadākāśaṃ- sky as a piece of hide; veṣṭayiṣyanti- will wrap up or envelop; mānavāḥ- men; tadā- then; devamavijñāya- without knowing Deva; duḥkhasya- of misery; antaḥ- end; bhaviṣyati- will occur

Verse meaning: End of miseries without knowing Deva will be possible, only when it is possible for men to envelop themselves with sky as a piece of hide.

The message is that miseries will not expire till one realises the Ātmā; no amount of prayers to Devas, no method of propitiation of deities and no number of pilgrimages to holy places will be effective in eliminating one’s miseries of worldly life. They can only be ended by realising the ultimate principle of Ātmā. That is why Muṇḍaka states in verse 1.2.7 that Yajñas (यज्ञ) with inferior Karmas prescribed in Purāṇas are fragile rafts to cross the ocean of worldly miseries.

Ṛsi Śvetāśvatara propounded this knowledge in the past, to Sannyāsins of the highest order. The Upaniṣad ends by an instruction that these teachings should be given, only to those sons and disciples who are well composed; such teachings will shine, only in those who have supreme devotion to the Deva (Ātmā) and the Guru.

Readers can contact the author by email at: karthiksreedhar@gmail.com