![]()

In this part of the series ‘The Science of Upaniṣads’, we take up for study, the Chāndogya Upaniṣad (छान्दोग्य). Previously we studied Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad and as an introduction to that study we had made the following observations defining the perimeters of our analytical reach in unravelling the scientific spirit of the Upaniṣadic thoughts.

“Upaniṣads are not like ordinary spiritual texts which dwell on glorification and appeasement of an almighty god through prayers, rituals and offerings, with an intention to secure protection, prosperity, happiness and long life. The primary concern of Upaniṣads is not the physical life as such, but the ultimate principle that sustains the physical life. Upanishads recognize the existence of an entity beyond the phenomenal world. They advance the concept of reality from a relative plain to the absolute state, to the reality that is free from all limitations of time and space. This advancement is the greatest achievement that Indian meditative mind accomplished and it is the greatest ever height that human mind scaled in speculative thinking. It was with this advancement that, in India, mere spiritual thinking graduated into pure philosophical deductions.

It is therefore imperative that any attempt to understand the teachings of Upaniṣads must be with due consideration for this unique feature inherent in them. Any alternative attempt employing the traditional tools of interpretation is unwelcome as it would only obscure the scientific spirit of the Upaniṣads and degrade their sublime teachings to mere theological compositions. Moreover, being extracts from other three parts of the Vedas, most of the Principal Upaniṣads contain some portions that do not fit well with the main theme under discussion in that particular Upaniṣad. Therefore, while interpreting the Upaniṣads to derive lessons therefrom, these portions have to be omitted from detailed consideration. In the present endeavour we keep in mind these observations as a guide in explaining the contents of each Upaniṣad. That means, we concentrate on those teachings that a rational mind should take note of and assimilate into its own cognitive constitution; in this process we simply ignore those contents which are rather ritualistic or purely mythological in nature.”

We abide by this observation, in considering Chāndogya Upaniṣad here and also all the remaining Principal Upaniṣads later. This Upaniṣad comprises of the last 8 chapters of the Chāndogya Brāhmaṇa; obviously it contains 8 chapters. Each chapter is divided into sections and each section contains a number of verses. So, a verse is identified by chapter, section and verse number respectively like 6.2.1. In size this Upaniṣad comes next to Bṛhadāraṇyaka. Sage Uddālaka Āruṇi whom we have seen in Bṛhadāraṇyaka asking questions on the principle that holds together and rules from within all beings, is the leading figure in this Upaniṣad. Here we see him teaching his son Śvetaketu about the ultimate principle. His teaching is the most important part of this Upaniṣad and it forms the contents of chapter 6. The famous declaration of ‘Tattvamasi’ is also found in this chapter, as uttered by Uddālaka Āruṇi.

Chapter 1

This chapter contains 13 sections, of which the first opens with a call to meditate upon the syllable ‘Om’. What is the reason for such a call? The syllable ‘Om’ represents the Ultimate Principle of Ātmā which is SAT-CHIT-ĀNANDA in essence. Ātmā is free from all dualities like pleasure-pain, affection-aversion, heat-cold, ups-downs, etc. that define the diversity of physical manifestation. It is these dualities that cause the miseries in the worldly life; when we are felled by them we are subjected to miseries. As such, in order to enjoy sustained happiness in life we have to keep ourselves insulated against the strike of these dualities. Since Ātmā is free from all dualities, it is advisable to stay close to it as far as possible for this purpose. That is why we are asked to meditate upon ‘Om’ which is verily the symbol of the principle of Ātmā. We will see further details of ‘Om’ in chapter 2 below.

Verse 1.1.10 declares that only those actions that are performed with knowledge, faith and meditation is more efficacious (1.1.10). This is because such performances extract the best from us due to the full concentration of all our faculties.

Section 2 speaks of rivalry between Devas and Asuras, which we may understand as the unending conflict between two opposite forces in every being, which give rise to various actions of different nature. A similar description can be seen in Bṛhadāraṇyaka 1.3 also.

Sections 3 to 13 of the 1st chapter speak about the different objects of meditation of ‘Om’ and related topics, which are of little interest to us, as our objective is to unravel the scientific spirit in the Upaniṣad. So we now move on to Chapter 2.

![]()

Chapter 2

In this chapter we go straight to section 23 since the preceding ones are not of much philosophical relevance. Verse 2.23.1 sets out the collection of laws (धर्मस्कन्ध) one should abide by, for leading a virtuous life; they are (i) Sacrifice, Study and Charity (yajña, adhyayana, dāna – यज्ञ, अध्ययन, दान); (ii) Austerity (tapas); and (iii) Chastity and Living in preceptor’s house (brahmacarya and ācāryakulavāsī – ब्रह्मचर्य, अचार्यकुलवासी). All these lead to the world of the virtuous; but, only one who is firm in Brahma attains immortality.

In verses 2.23.2 and 2.23.3 we see a description of how the syllable ‘Om’ evolved from intense meditation by Prajāpati. The worlds on intense meditation gave forth the Vedas (प्रजापतिर्लोकान् अभ्यतपत् तेभ्योഽभितप्तेभ्यः त्रयी विद्या संप्रास्रवत् – prajāpatirlokān abhyatapat tebhyoഽbhitaptebhyaḥ trayī vidyā saṃprāsravat -2.23.2), which in turn gave forth the ‘bhur-bhuva-svaḥ’ in the same manner. It is these three sounds that finally gave forth the syllable ‘Om’ through the same process. Thus ‘Om’ is the abstraction of all the Vedas and all the worlds; ‘Om’ is all this (ओंकार एवेदं सर्वम् – oṃkāra evedaṃ sarvam – 2.23.3).

Chapter 3

This chapter starts with an enquiry into the essence of various objects in this phenomenal world and finally comes to the conclusion that all this is Brahma only (सर्वं खल्विदं ब्रह्म – sarvaṃ khalvidaṃ brahma – 3.14.1); everything originates from it, exists in it and finally merges into it. One has to meditate upon it calmly, without being disturbed by dualities such as affection-aversion and pleasure-pain. Since man consists in his will, he would become what he wills. So he must do the meditation with a firm determination. In the following three verses, viz. 3.14.2, 3.14.3 & 3.14.4 we see what this Brahma is. It is Ātmā who is absolute cognizance, having vital air (प्राण – prāṇa) as body, brilliance as appearance and ether (आकाश- ākāśa) as form; within him are all deeds, all desires, all smells, all tastes and he pervades everything here; he is calm and also unattached (3.14.2). (The phrase, ‘all deeds, all desires….’ means that he is the source of these all. Since every phenomenal thing exists in opposites, an entity that is declared to be the source of all these should contain none of these; they should cancel each other. Ātmā is therefore devoid of all these phenomenal things). This is the very same Ātmā that is in our inner heart of consciousness; smaller than a corn, barley, or the kernel of mustard seed and at the same time greater than the earth, the sky and all these worlds (3.14.3). One attains to Ātmā, on leaving this phenomenal existence (3.14.4).

The implication is that Ātmā is the subtlest of the subtle and grossest of the gross; it pervades all beings and things. Ātmā is one without a second; it is an incessant continuity, without any break, pervading the entire universe. The description about body, appearance, etc. is an indication that it is not graspable by sense organs.

Chapter 4

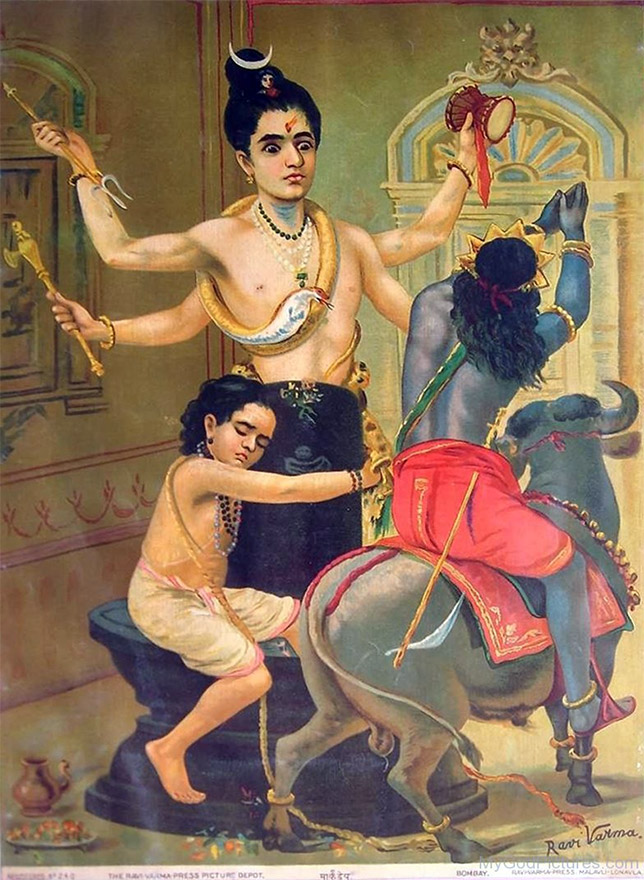

In this chapter we see some stories about how certain people sought to know the Brahma. The most interesting of these is that of Satyakāma Jābāla (4.4.1 to 4.9.3). The boy Satyakāma wanted to be initiated into religious studies; in order to approach a teacher for the purpose, he needs to know the name of his clan (family). He asked his mother; her reply was very strange. She said, “I do not know, my child, of what family you are. In my youth I used to move about much, as a servant and then I conceived you. So, I do not know of what family you are. But I am Jabālā and you are Satyakāma; so mention yourself as Satyakāma Jābāla”. He went to the teacher by name Gautama, son of Haridrumata and requested to be instructed. About his clan, he revealed what his mother said. Gautama was impressed by his honesty and took him as a student. Then Gautama chose four hundred lean and weak cows and asked Satyakāma to go with them. While going with the cows, Satyakāma vowed that he would return only when the number of cows rises to thousand. When the cows were thousand in number, the Bull in the herd asked Satyakāma to take them to teacher’s house. The Bull also instructed him on one quarter of Brahma, ‘Brahma is Radiant’ (prakāśavān – प्रकाशवान्). The radiant Brahma consists in the four directions. Satyakāma learned about the other three quarters of Brahma from Fire, Haṃsa (flamingo) and Madgu (water-bird). They respectively taught him about Brahma as Endless (anantavān – अनन्तवान्), Effulgent (jyotiṣmān – ज्योतिष्मान्) and as the Abode (āyatanavān – आयतनवान्) respectively.

Having thus learned about Brahma, Satyakāma returned to his teacher, who found him to be shining like one who knew Brahma. Satyakāma told him that he was taught about Brahma by those other than humans; but he still wanted to be taught by the teacher as he had heard that knowledge learnt from the teacher is the best. The teacher indeed taught him, but it was same as what he had already learned. With this story we now pass over to the next chapter.

Chapter 5

The first section of this chapter says about a dispute between the organs of speech, eyes, ears, mind and breath, on who among them is the best. They approached their father Prajāpati to resolve the dispute. He told them, “He is the best on whose leaving, the body becomes the worst”. Then, each of them in turn left the body and stayed away for a year; when finally, the breath was about to depart, the other organs began to be detached from their respective places. Thus, it was established that breath (prāna) is the best among them (5.1.1 to 5.1.15). The rest of the chapter is full of contents of the nature of mythological descriptions having no direct declarations of philosophical nature and therefore we skip them to move on to the next chapter.

![]()

Chapter 6

This is the most important chapter of the Chāndogya Upaniṣad; for, it takes us to the most express declarations of Ātmā and Brahma. These are revealed in a conversation between Śvetaketu and his father Uddālaka Āruṇi. When Śvetaketu approached the age of initiation into Vedic learning (ie. 12 years), his father asked him to live the life of a religious student (ब्रह्मचारि). He wanted the son to become a real Brāhmaṇa rather than a Brāhmaṇa for namesake (ब्रह्मबन्धु – brahmabandhu); in their family there had been none ever who was only a Brahmabandhu. Having been so instructed by his father, Śvetaketu went to a teacher and lived there for 12 years studying Vedas. At the age of 24 he returned to his father as a young man arrogantly thinking that he had learnt everything in the Vedas. The father sensed his conceit and wanted to demolish it by showing that he did not have the real knowledge; for, those who have the real knowledge cannot be arrogant about their learning; Vedic knowledge is only a tool to attain that knowledge. So he asked, “Dear son, did you ask for that instruction by which the unheard becomes heard, the unperceived becomes perceived and the unknown becomes known? (6.1.2 & 6.1.3)”

“… तमादेशमप्राक्ष्यः येनाश्रुतं श्रुतं भवति अमतं मतं अविज्ञातं विज्ञातं इति …… (6.1.2 & 6.1.3)

“…. tamādeśamaprākṣyaḥ yenāśrutaṃ śrutaṃ bhavati, amataṃ mataṃ avijñātaṃ vijñātaṃ iti …)

What the father asks about is the knowledge of the ultimate principle that cannot be grasped by the ordinary faculties of cognition. The implication of the phrase ‘unheard becomes heard, etc.’ is that this particular knowledge cannot be acquired by physical faculties of cognition. It is also indicated here that knowledge of Vedas is fruitless if, with it, one is not able to know the ultimate principle. Śvetaketu was unaware of such a type of knowledge, though he had studied the Vedas properly. So he desired to know what kind of instruction that was. The father explains thus:

“यथा सोम्यैकेन मृत्पिण्डेन सर्वं मृन्मयं विज्ञातं स्यात् वाचारम्भणं विकारो नामधेयं मृत्तिकेत्येव सत्यम्” || 6.1.4 ||

“yathā somyaikena mṛtpiṇḍena sarvaṃ mṛnmayaṃ vijñātaṃ syāt vācārambhaṇaṃ vikāro nāmadheyaṃ mṛttiketyeva satyam” (6.1.4)

“यथा सोम्यैकेन लोहमणिना सर्वं लोहमयं विज्ञातं स्यात् वाचारम्भणं विकारो नामधेयं लोहमित्येव सत्यम्” || 6.1.5 ||

“yathā somyaikena lohamaṇinā sarvaṃ lohamayaṃ vijñātaṃ syāt vācārambhaṇaṃ vikāro nāmadheyaṃ lohamityeva satyam” (6.1.5)

“यथा सोम्यैकेन नखनिकृन्तनेन सर्वं कार्ष्णायसं विज्ञातं स्यात् वाचारम्भणं विकारो नामधेयं कृष्णायसमित्येव सत्यं एवं सोम्य स अदेशो भवतीति” || 6.1.6 ||

“yathā somyaikena nakhanikṛntanena sarvaṃ kārṣṇāyasaṃ vijñātaṃ syāt vācārambhaṇaṃ vikāro nāmadheyaṃ kṛṣṇāyasamityeva satyaṃ evaṃ somya sa adeśo bhavatīti” (6.1.6)

Meaning: ‘That instruction, my dear, is just as: (i) by a single lump of earth, all that is earthen becomes known as mere modifications expressed in names based on words, the truth being that all is earth only;

(ii) by a single ingot of gold, all that is golden becomes known as mere modifications expressed in names based on words, the truth being that all is gold only; and

(iii) by a single nail-cutter, all that is made of iron becomes known as mere modifications expressed in names based on words, the truth being that all is iron only’.

The implication is that there exists only one entity and all that is here is only modifications of that entity expressed in names and forms. If that entity is known, everything it manifests also is known. It does not however mean that one who realises that entity would know all nuances of the physical world; for example, such a person cannot be expected to speak all languages of the world or to do a complicated neurosurgery. He would only know the truth of the world so that he gets a vision to view the whole world to be a part of his being and vice versa. This will enrich his life with everlasting peace and happiness. Upaniṣads consistently declare that Ātmā is this entity. We have seen this declaration in Bṛhadāraṇyaka and will see it again and again in course of our study. Ātmā is ‘SAT-CHIT- ĀNANDA’ (‘सत् चित् आनन्द’ – ‘sat-cit-ānanda’) in essence. SAT is that which does not have a state of non-existence (Bhagavad Gīta – 2.16), CHIT is pure, absolute consciousness and ĀNANDA is transcendent bliss. Why Ātmā, that is said to be the ruling force of the universe, is ‘SAT-CHIT- ĀNANDA’? Because, the whole universe is motivated, in all its activities, by the urge either to exist or to express or to enjoy. SAT denotes existence, CHIT denotes cognition and expression, and Ānanda denotes enjoyment. So, Ātmā is ‘SAT-CHIT- ĀNANDA’; it is only a logical abstraction of the urge behind all the actions in this universe. Now, in the next section we see how from SAT the entire universe emerged.

In 6.2.1 and 6.2.2 it is declared that only SAT existed in the beginning and nothing else; from it, all came forth. It was not nothingness that existed in the beginning as believed by some, since nothing can come forth from nothingness. In the beginning, energy (tejas) emerged from SAT, from energy, water emerged and from water, food (annam) emerged; it was from annam that all beings came forth (6.2.3 & 6.2.4). (Food or annam is simply that which cater to the emergence of beings; it need not be something eaten). At this point, it may be noted that to the modern science atoms are the fundamental particles of matter constituting the universe. Atoms are only ‘drops’ of energy separated into oppositely charged particles. Thus, it is evident that separation of energy into opposites is the secret of manifestation of the phenomenal world and this process presupposes presence of energy.

Since from SAT, the three entities of energy, water and food emerged progressively resulting in emergence of beings, every being contains all the three; and they also contain the principle of SAT which sustains their very existence (6.3 & 6.4). Annam when consumed becomes three-fold, viz. the grossest becomes faeces, the subtlest becomes mind and the middle part becomes flesh. Water consumed similarly becomes urine, prāṇa and blood respectively. Energy in the same way becomes bone, speech (vāk) and marrow. Thus, mind consists in annam, prāṇa in water and speech in energy (6.5.1 to 6.5.4 and 6.6).

In section 6.7 Uddālaka Āruṇi demonstrates to his son Śvetaketu without annam the mind does not work properly. Śvetaketu was asked not to take food for fifteen days; he did so and then, he was unable to remember the Vedas he studied. Later he ate and was able to remember all. Uddālaka concludes by asserting that mind consists in annam, prāṇa consists in water and speech consists in energy (अन्नमयं हि मन, आपोमयः प्राणः, तेजोमयी वाक् – annamayaṃ hi mana, āpomayaḥ prāṇaḥ, tejomayī vāk – 6.7.6).

Uddālaka continues his teaching in 6.8 by explaining what sleep means. In sleep one is fully possessed by SAT which is his origin (स्वं अपीतो भवति, तस्मात् एनम् स्वपितीत्याचक्षते – svaṃ apīto bhavati, tasmāt enam svapitītyācakṣate – 6.8.1). In deep sleep, even the mind ceases to work and rests on prāṇa (प्राणबन्धनं हि मन – prāṇabandhanaṃ hi mana – 6.8.2). When mind does not work, it is obvious that speech also will not work. So, in sleep, only prāṇa is active, apart from SAT, the origin.

Then, in 6.8.3 to 6.8.5, he once again repeats what he said in 6.2.3 and 6.2.4 that annan is the cause of beings, water is the cause of annam and energy is the cause of water; all these are effects of some cause and nothing here occurs without a cause (नेदं अमूलं भवति – nedaṃ amūlaṃ bhavati – 6.8.3 & 6.8.5). But, SAT is the cause of all; everything emerges from SAT, exists in SAT and finally merges into SAT. When a man departs from here, his speech merges in mind, the mind in prāṇa, the prāṇa in energy and the energy in the highest entity (अस्य पुरुषस्य प्रयतः वाङ्मनसि संपद्यते, मनः प्राणे, प्राणस्तेजसि तेजः परस्यां देवतायाम् – asya puruṣasya prayataḥ vāṅmanasi saṃpadyate, manaḥ prāṇe, prāṇastejasi tejaḥ parasyāṃ devatāyām – 6.8.6).

In the next verse, it is clarified that that this highest entity is Ātmā which is subtleness itself and therefore, SAT, which, as we have seen, as the source of energy, prāṇa and annam, is implied to be a constituent of Ātmā. The declaration that on leaving from here or, in other words, on shedding this body, every being merges into Ātmā, is a very important one. It scotches all talks about rebirth of the same individual. Personal identity is lost on merging with Ātmā which is an incessant, all-pervading entity, without a second. This fact finds expression in Bṛhadāraṇyaka 2.4.12 also; we will see it again in 6.9, 6.10 ibid also. Now coming to 6.8.7, the verse goes like this:

स य एषोഽणिमा ऐतदात्म्यमिदम् सर्वं तत् सत्यम् स आत्मा तत्त्वमसि श्वेतकेतो …|

(sa ya eṣo’ṇimā aitadātmyamidam sarvaṃ tat satyam sa ātmā tattvamasi śvetaketo.)

Meaning: ‘He (that Great Being mentioned in the previous verse) is absolute subtleness (subtle essence) which inheres in all that is here; that (all that is here) is Satyam, He (the Great Being) is Ātmā; you are that (Satyam), O, Śvetaketu.

This sentence is seen repeated in verses 6.9.4, 6.10.3, 6.11.3, 6.12.3, 6.13.3, 6.14.3 and 6.15.3. Incidentally, it is the very phrase ‘तत्त्वमसि’ ‘(tattvamasi)’ appearing here, that is designated as one of the four Mahāvākya(s) in the Upaniṣads.

The word ‘Satyam’ is usually translated as truth or simply ‘true’. But, it is not the case; ‘Satyam’ has got specific philosophical meaning. That which has SAT is Satyam; this is explained in detail in 8.3.5 of this Upaniṣad as well as in 5.5.1 of Bṛhadāraṇyaka. Further, in 2.6 of Taittirīya Upaniṣad it is declared that whatever here is only Satyam. We must keep these in mind while trying to understand the real import of the verse 6.8.7. The verse means that Ātmā is SAT; it pervades all that is here; therefore, every being is Satyam; O, Śvetaketu, you are that (what is Satyam).

In 6.9, Uddālaka explains to his son further about how personal identity is lost on being merged with the Supreme Entity as mentioned in 6.8.6, by citing the example of the process of making honey by honey bees. The bees collect nectar from various trees and make honey mixing all; when honey is produced, the nectar of a tree cannot distinguish itself from the nectar of other trees; its personal identity is lost. All beings, whether it be a tiger, or lion, or wolf, or a pig, or insect, or gnat, or mosquito, all continue their existence in the same manner. This means that they exist as merged in the Supreme Entity without knowing their personal identity, as in the case of nectar of various trees in the honey. The verse says as follows:

‘त इह व्याघ्रो वा सिंहो वा वृको वा वराहो वा कीटो वा पतङ्गो वा दंशो वा मशको वा यद्यद् भवन्ति तदाभवन्ति’ || 6.9.3 ||

ta iha vyāghro vā siṃho vā vṛko vā varāho vā kīṭo vā pataṅgo vā daṃśo vā maśako vā yadyad bhavanti tadābhavanti. (6.9.3)

आभवन्ति (ābhavanti) = continue existence.

In spite of this express declaration and the enlightening examples to the effect that on merging with Ātmā personal identity of beings is lost, some interpret this verse to mean that these creatures retain their identity and take birth again as the same beings. This is because they misunderstand the meaning of ‘ābhavanti’ as continuance of existence ‘with the same identity’, the italicized part being their inadvertent contribution. It may be specifically noted that this verse is followed by the declaration in 6.9.4 that the said Supreme Entity is Ātmā and all, as in 6.8.7.

We find further elaboration of this idea in 6.10 also, the example quoted being that of rivers merging with the sea and losing their personal identity. Till the end of the chapter, the same idea is dealt with again and again.

Chapter 7

This chapter is about Sanatkumāra teaching Nārada on the enquiry into the ultimate principle of Ātmā. Nārada approaches Sanatkumāra saying that he knows all the Vedas and ancillary literature, but still has not overcome sorrow as he does not know the Ātmā. This may remind us about the context and relevance of the question Uddālaka Āruṇi was asking his son Śvetaketu in 6.1.2 above. Now, Nārada similarly asks for that instruction which would carry him beyond sorrow. Accordingly, Sanatkumāra teaches Nārada starting with the possibilities and limitations of meditating upon various objects. Initially he proposes ‘Names’ as the object since he says Vedas, etc. are mere names and Nārada knows only them. Step by step he moves on to various other objects like speech, mind, imagination, etc. and finally reaches prāṇa (vital force). He says that Prāṇa is the ultimate of all the other objects having physical origin, since it is Prāṇa that sustains all of them, all organs and faculties and also the beings themselves, and at the same time, Prāṇa is independent of them all. Therefore, Prāṇa is everything (as far as physical existence of man is concerned); one who knows thus is called an Ativādi (अतिवादि – 7.15.4). Ativādi is one who speaks assertively. In order to speak assertively one should know the truth (7.16.1). One knows by reflecting only; nobody knows without reflecting (7.18.1). This declaration is very important; our senses do not gather knowledge directly from anywhere. They obtain signals and these signals are interpreted by mind (manas-मनस्) under the supervision of intelligence (buddhi-बुद्धि) by accessing and comparing with the already existing data in memory (citta-चित्त); it is through such reflecting that the ‘knowing person within’ (ahaṃkāra-अहंकार) knows. Incidently, these four, namely manas, intelligence, memory and the knowing person, are collectively known as ‘inner organs of action’ (antaḥkaraṇa-अन्तःकरण).

In the next verse, it is said that reflection is possible if only we have composure (7.19.1). To have composure, steadiness of mind is needed (7.20.1). To be steady, one should be active so that no work is left undone (7.21.1). One would be active, when he gets happiness by acting; if happiness is not there he would not act (7.22.1). Everlasting happiness exists in that which is infinite in essence (7.23.1). Infinite is that wherein nothing else is seen, heard or cognized; (when there exists nothing else, there is no need for desire for anything or action to acquire it; as a result there is no room for unhappiness); that which is infinite is immortal and that which is finite is mortal (7.24.1). The infinite and immortal is Ātmā which pervades all and everything; whatever here has emerged from Ātmā (7.25.2). Thus knowing the ultimate principle of Ātmā, Nārada was relieved of his sorrows.

This episode of Nārada justifies Uddālaka’s criticism of Śvetaketu’s presumed conceit.

Chapter 8

Now we enter the last chapter of this Upaniṣad. It contains a very detailed discussion on Ātmā and Brahma. The chapter opens with a direction about what should be sought for and known; it is that which is there in the space inside the lotus-abode within our Heart (8.1.1).

.. यत् इदं अस्मिन् ब्रह्मपुरे दहरं पुण्डरीकं वेश्म दहरोഽस्मिन् अन्तराकाशः तस्मिन् यदन्तः तदन्वेष्टव्यं तद् वाव विजिज्ञासितव्य्म् … || 8.1.1 ||

… yat idaṃ asmin brahmapure daharaṃ puṇḍarīkaṃ veśma daharoഽsmin antarākāśaḥ tasmin yadantaḥ tadanveṣṭavyaṃ tad vāva vijijñāsitavym … (8.1.1)

ब्रह्मपुर (brahmapura) means Heart; but it is not the heart of blood circulation. It is the centre of consciousness, which in modern scientific parlance is Thalamus. What is the authority for this claim? Verse 3.6 of Praśna (प्रश्न) Upaniṣad says that the Heart, which is supposed to be the seat of Ātmā, is where the nerves are connected. Ātmā, we know, is pure consciousness in essence (in addition to existence and bliss) and therefore, its seat is the centre of consciousness. This is Thalamus, because, it is the nerve centre and is considered to be the switch board of information. All signals come to it and then transmitted to the concerned organs. Through the nerves emanating from the Thalamus, consciousness pervades throughout the body. Thus, Ātmā is in the Heart and the verse says that it is that (Ātmā) which should be sought for and known. Most interpreters take the word ‘Heart’ to mean the heart of blood circulation and consequently misinterpret nāḍi (नाडि) in the scriptures as artery instead of the true meaning of ‘nerve’; this mistake results in misleading the understanding and conveying the true message of the Upaniṣads. In this connection please also see the contents of 8.3.3 mentioned below.

From the description given in verse 8.1.3, it is amply clear that what is there in the lotus-abode is Ātmā. The verse states that the space within the said lotus-abode is as large as the space outside and it contains whatever here in the sky and in the earth and still more. That means everything outside is contained within. The phrase ‘and still more’ indicates that the world outside is an expression of the entity within and that there is scope for further expression.

The usage ‘lotus-abode’ is also meaningful; as lotus is not wet by water, though it is established in water, so is the entity in this abode, namely, Ātmā.

In 8.1.5, it is declared that Ātmā is not deteriorated by old age when the body gets old and does not become dead when the body is dead; the Heart is Satyam and therein are established all the wishes; but Ātmā is free from evils, old age, death, sorrows, hunger and thirst; whatever he wills and resolves, they all come true. The expression, ‘Ātmā is free from evils, etc.’ means that Ātmā is devoid of all dualities of evil-virtue, pleasure-pain, etc; it is pure (serene) SAT-CHIT-ĀNANDA which transcends all the dualities.

In continuation of what is said in 8.1.1, it is stated in 8.3.3 that this Ātmā is in the Heart. The etymology of the word ‘Heart’ is given here as: हृदि + अयम् = हृदयम् (hṛdi + ayam = hṛdayam). ‘hṛdi’ means in the inner chest; ayam indicates Ātmā. Therefore, Heart or hṛdayam means the inner chest where Ātmā is seated. Thalamus in Greek also means ‘chamber’.

The phrase ‘Ātmā is in the Heart’ has to be understood thus: ‘The subtlest physical form of a living being is a cell. It contains some physical features and also the coded information on genetic qualities and on hereditary traits. It also contains the energy of consciousness which reads and interprets this information and also motivates physical functions in furtherance thereof. This pure consciousness is the CHIT part of the Ātmā and the physical part wherein it is situated is the Heart. As the cell multiplies and grows into a full-fledged being, this Heart also develops into its matured form and along with it a net-work of nerves is also established, through which Ātmā pervades the entire physique of the being. Therefore, Ātmā is not exclusively located in the Heart, though it is stated, ‘Ātmā is in the Heart’. Even otherwise, the SAT part of Ātmā is already there pervading throughout the being, supporting its physical existence’.

Verse 8.3.4 says about the body and the serene being within. From 8.1.5 we know that this serene being is Ātmā. So, the reference here is to Ātmā holding the body. This is Brahma. It is asserted in this verse that the name of the said Brahma is ‘Satyam’. When the body is dead, the ‘CHIT’ part of Ātmā withdraws itself into the supreme unified form of SAT-CHIT-ĀNANDA.

The ‘Satyam’ is explained in 8.3.5 thus: तानि ह वा एतानि त्रीण्यक्षराणि सतीयमिति तद्यत्सत्तदमृतं अथ यत्ति तन्मर्त्यं अथ यद्यम् तेनोभे यच्छति …. (tāni ha vā etāni trīṇyakṣarāṇi satīyamiti tadyatsattadamṛtaṃ atha yatti tanmartyaṃ atha yadyam tenobhe yacchati … )

Meaning: ‘It (Satyam) is these three letters, sa, ti, yam; sa is immortal, ti is mortal and yam holds them both together’. We may compare this explanation of Sayam with that given in 5.5.1 of Bṛhadāraṇyaka; both convey the same idea. Moreover, this definition conforms well with the declaration in 2.3.1 of Bṛhadāraṇyaka that Brahma has two forms, viz. the mortal and immortal, etc. As against this notion of Brahma, it may be noted that Ātmā is absolutely immortal.

It is further taught in verse 8.4.1 that Ātmā keeps everything in this universe in proper position so that they maintain their individual existence and that it also serves as a binding force establishing an inter-connection among them all; it is not overcome by day and night, old age and death, sorrow and good/bad works. These are only a further enlightenment on what we have already understood about Ātmā.

The thoughts about the Heart and the nerves are further continued in section 8.6. In verse 8.6.1 it is stated that the nerves in the Heart are extremely fine in nature and are of various colours such as brown, white, blue, yellow and red. Verse 8.6.3 says that when a person is fast asleep, in perfect rest, his consciousness withdraws from the sense organs and remains within the nerves; he is then possessed solely by the brilliance of Ātmā; then he knows not sorrows.

Verse 8.6.6 tells us about the number of nerves. The verse is,

शतं चैका हृदस्य नाड्यः तासां मूर्धानमभिनिःसृतैका

तयोर्ध्वमायन्नमृतत्वमेति विष्वङ्ङन्या उत्क्रमणे भवन्ति || 8.6.6 ||

śataṃ caikā hṛdasya nāḍyaḥ tāsāṃ mūrdhānamabhiniḥsṛtaikā tayordhvamāyannamṛtatvameti viṣvaṅṅanyā utkramaṇe bhavanti (8.6.6)

Meaning: ‘There are 101 nerves attached to the Heart, of which one goes up; moving by that nerve, one attains immortality. All other nerves lead to different directions’.

The same verse is seen repeated in Kaṭha (कठ) Upaniṣad at 6.16 and the same topic is dealt with in detail in 3.6 and 3.7 of Praśna (प्रश्न) Upaniṣad. The Praśna says that the number of main nerves is 101 which branch into secondary and tertiary nerves, the entire total being 72 crores and 72 lakhs. The one that refers to in the above verse is obviously a main nerve. Since its direction is upwards, it must be inferred to be the communication highway of the brain. The upward movement through the nerve, mentioned in the verse, must be directed to the brain which actually is the centre of knowledge. ‘Going upward’, therefore, means ‘going to the brain’ which, in turn, implies pursuing knowledge. Cumulatively, the declaration in the verse would mean that by acquiring knowledge one would be able to attain immortality. The remaining nerves, on the other hand, are entrusted with bodily functions; therefore ‘following them’ means indulgence in worldly pleasures, which would lead us astray. How do we attain immortality by acquiring knowledge? When we are enlightened on the secret of existence, we would realise that it is foolish to be overcome by Kāma (intensified attachement) and thus we are saved from falling into worldly miseries. Immortality is that state wherein Kāma does not overtake us. Death simply means capitulation to Kāma. We will see more about this in later articles.

Now, from 8.7 to the end of the Upaniṣad’, the topic is Prajāpati imparting knowledge to Devas and Asuras. Prajāpati once declared thus: ‘what one should seek after and know is the Ātmā which is free from evils, decay, death, sorrow, hunger, thirst; his wills and resolves are accomplished; whoever seeks and knows him, attain to all worlds and all desires’. Devas and Asuras heard about this. Having been desirous of fulfilling their desires and of winning all the worlds, they decided to approach Prajāpati for the specified instruction. Accordingly Indra from among the Devas and Virochana (विरोचन) from among the Asuras met Prajāpati with the prayer for the desired instruction. They stayed with Prajāpati for long thirty-two years; at last Prajāpati instructed them, “I have said about the Puruṣa who is seen in the eye; this is Ātmā, immortal and fearless; this is Brahma” (8.7.4). At this, Devas and Asuras raised a doubt whether ‘this Puruṣa is the one who is seen in the mirror or in water’. Prajāpati clarified that ‘it is he who is perceived in all these’. He then asked them to look at themselves in a cup of water; they did so and saw themselves as they were. He again asked them to repeat the same task after adorning, dressing and cleaning themselves well; they did so and found themselves as they were and told Prajāpati as such. Realising that these two were matured enough to see beyond the physical appearance, Prajāpati sent them back saying that they saw what they sought. They went away fully satisfied in their hearts (8.8.3). Virochana spread this instruction among the Asuras; consequently, Asuras still decorate the body of the dead with food, dresses and ornaments with the hope that these would earn for him the boons of the next world (8.8.5).

But, Indra, before reaching the Devas, found some difficulty in the instruction. He thought, “If the Ātmā becomes well dressed, adorned and cleaned as the body is, then if the body is dead Ātmā will also die. But Ātmā is immortal”. So, he found the instruction unacceptable and consequently returned to Prajāpati for further enlightenment. This time also he had to spend thirty-two years with Prajāpati. This episode recurred several times with the total stay rising to one hundred and one years, with Prajāpati uplifting Indra each time to new levels of awareness about Ātmā.

At last Prajāpati said to him, “Indra, this mortal body is held by Death; but it is the abode of the immortal, incorporeal Ātmā. The corporeal one is seized by pleasure and pain, but the incorporeal is not so (8.12.1). Ātmā causes the eyes to see, the nose to smell, the ears to hear, the speech to speak and the mind to think (8.12.4, 8.12.5). Those who meditate upon this Ātmā obtain all worlds and all desires (8.12.6)”.

The Upaniṣad winds up the instructions with the advice that the one who, having studied the Vedas in the proper manner and having discharged the duties of a house-holder, lives a life devoid of sensual enjoyment, by restraining the senses and at the same time, refrain from causing undue injuries to other creatures, reaches the world of Brahma and never returns. The implication is that he transcends all the dualities and resultantly, feels complete calm and peace; he gets established in it. The insistence on spiritual enlightenment through proper study of the Vedas and indifference to physical pleasures may be noted. These two precisely define the state of detachment and equanimity constituting the world of Brahma. One who reaches this world will never return, simply because of the experience of pure bliss therein which can never be matched by any physical pleasure; he will realise how lowly the pursuit of physical pleasure is and will therefore remain therein with full contentment.

Prior parts in this series by the author, Karthikeyan Sreedharan:

The Science of the Upanishads

The Science of Brihadaranyaka Upanishad